Information disclosure is a type of vulnerability in which a system inadvertently exposes confidential information. This post walks through an example of this flaw by looking at how environment variables can be misunderstood and misused in web applications. This post will revisit the best practices and conclude with actionable advice for developers.

Leaking Secrets describes an information disclosure flaw in which an application exposes sensitive credentials or API keys to an adversary. The OWASP Top Ten 2017 categorizes this flaw as “Sensitive Data Exposure”. This post will discuss how this can be exploited with a case study of a vulnerable and misconfigured middleware gem running on a rails application. These types of issues can lead to a data breach for an enterprise, resulting in significant financial and reputation harm. These issues are observed frequently, as Infrastructure as Code (IaC) and Cloud speed enable DevOps personnel to quickly spin up new web applications and environments unchecked. If you are a developer working with Rails, you need to be aware of these issues. If you’re a pentester working with web applications, you’ll find this information useful and (my hope) be better able to protect your clients.

Exposing secrets over the public Internet in your web application is exactly what you never want to do. To the Rails developers reading this, a tip of the hat to the Rack-mini-profiler.

Rack-Mini-Profiler: The Good, Bad, Ugly

Rack-mini-profiler is a middleware gem used by Rack developers as a performance tool to improve visibility and speed in Rack-based web applications. The tool has value to the developer community and is highly regarded, as shown from this enthusiast:

rack-mini-profileris a a performance tool for Rack applications, maintained by the talented @samsaffron. rack-mini-profiler provides an entire suite of tools for measuring the performance of Rack-enabled web applications, including detailed drill downs on SQL queries, server response times (with a breakdown for each template and partial), incredibly detailed millisecond-by-millisecond breakdowns of execution times with the incredibleflamegraphfeature, and will even help you track down memory leaks with its excellent garbage collection features. I wouldn’t hesitate to say thatrack-mini-profileris my favorite and most important tool for developing fast Ruby webapps.

I recently discovered a deployment of a Rails application using Rack-mini-profiler in the wild, and it was eye-opening to see the security issues. I want to be clear that I’m not saying the gem has an inherent vulnerability; rather, it is a problem with how the middleware gem can be used or configured without proper security protections. So I set out to better understand how this could happen and the actual vulnerabilities observed. The culmination of this effort is an open-source project, “Hammer.” Hammer is an example of a vulnerable Rails application deployment that uses Rack-mini-profiler to leak API keys and sensitive information. It is vulnerable in the exact same way as a real-world application observed in the wild. It’s also a skeleton app that can be used to fork and experiment with sensitive variables in a safe way. In the process of building this tool I’ve learned a few things and want to share the lessons learned with the developer and InfoSec communities.

The Hammer Github site is here.

A light Hammer introduction is here.

Let’s do a quick tour of the capabilities of the Middleware that offers so many benefits to a developer but at the same time makes it an attractive attack target. You can follow along at the demo application for Hammer: https://preprod.rtcfingroup.com.

In the top left-hand corner, an “HTML Speed Badge” is rendered by installing this performance middleware gem. When the tool is installed the HTML speed badge can be used to profile any given page served by the Rails application.

Let’s navigate over the URL where the sensitive users are publicly accessible — https://preprod.rtcfingroup.com/users/. Note that these aren’t real users. They are randomly generated from a script included with the tool that simulates users. Take a look at the HTML speed badge in the top left corner and see how it has rendered the amount of time for the page to render.

Expanding the speed badge at /users/ shows the time in milliseconds spent rendering each page. Note the interesting SQL query for rendering users/index. Rack-mini-profiler creates a link that you can click on to get more information. Let’s take a look.

Below, you can see that Rack-mini-profiler displays detailed call stack query information. You can see the SQL query, file, and precise line that is rendering the users. This is great information for a developer who is trying to improve performance and identify bottlenecks in the application. But from an attacker perspective, this gleans valuable information such as SQL queries that could enable other vulnerabilities to be exploited. It is considered a standard security practice to never expose SQL queries client side. When I first saw this in the wild, I couldn’t believe what I was seeing. Rack-mini-profiler’s website states that the tool can be used to profile applications in development and production. That is why it is so important to ensure that exposing the SQL call stack query aligns with your organizational security policy for application development. When I first saw this, I didn’t know that there would be something far more interesting. Read below.

Rack-mini-profiler gem uses the “Pretty Print” Ruby class (pp) that can be found at the default URL by appending ?pp=help. It has a lot of nice features for developers such as memory profiling and garbage collection. The most interesting from a security perspective is pretty printing env.

№1: Dumping “env”

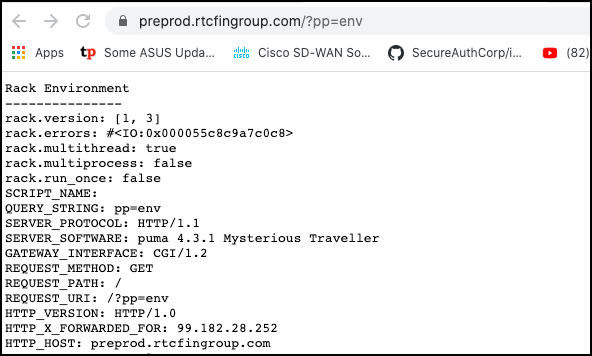

This env pretty print feature dumps all environment variables that are being passed to the Rails application. This includes the Rack Environment as shown below.

Taking a look at the Rack-mini-profiler source code for the profiler.rb, the code shows that it first dumps env by iterating through and printing the local variables stored in env. This correlates with the output shown above starting with “Rack Environment.”

№2: Dumping “ENV”

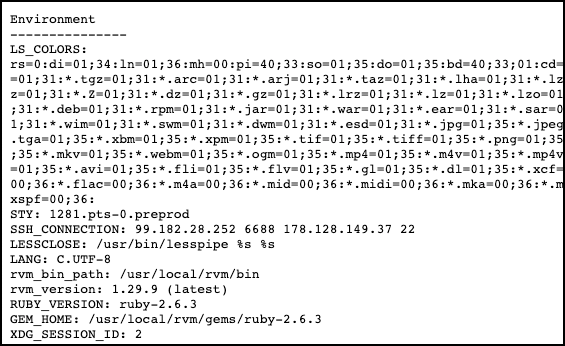

Second, it dumps the ENV constant by iterating through and printing the contents of this hash.

The screenshot below shows the start of dumping ENV constant hash from the sample vulnerable application, correlating with the second part of code starting with ENV.each do.

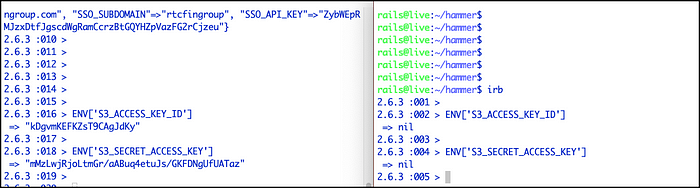

In this example, the Amazon S3 API keys have been stored in ENV, leaking them out to the public. This shows how dangerous it can be storing API secrets and other sensitive credentials within environment variables stored in the ENV constant hash. We’ll talk a little more about how this happens below.

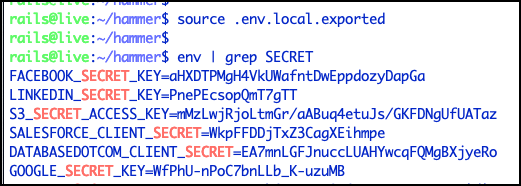

Taking this a step further, the sample application leaks a variety of different cloud API and secrets, including Facebook, Twitter, LinkedIn, and Google.

What are ENV and env in Ruby?

ENV is a hash-like class that Ruby uses to expose environment variables to our application. For example, PATH or HOME can be made available to our rails application. Rack-mini-profiler doesn’t have to do much to dump ENV because the constant is exposed upon the application launch. It is up to the developer to properly store, load, and secure ENV. ENV traditionally correlates with an environment variable and is more global than env. Each of these variables is listed as key/value pairs and they are usually used to share configuration.

All Rack applications such as Rails take a single argument which is a hash called env. The env is passed to the Rails application and stores information such as HTTP header, request, and server configuration. In comparison to ENV, env is more local to Rails.

The Vulnerability

Environment variables should never be used to store sensitive configuration information such as credentials and API keys. If they must be used, your security program should accept this risk, document it within your risk register, and provide appropriate security controls to mitigate the risk.

Much has been said about environment variables and their proper usage. The Twelve-Factor App manifesto states that environment variables should be used to store configuration elements such as credentials to external services such as Amazon S3 or Twitter.

I do not agree with this. Following this practice will increase the business risk to your company.

The example application shows how easy it can be for developers to make a mistake and inadvertently expose sensitive API keys such as AWS that allow data breach. This application was created to mimic a production environment found in the wild that was secured after enumerating the issues described above. It is the case that Rails developers can use different environments such as production, QA, or development. The Rack-mini-profiler is designed to be used in any of these environments. The exposed environment variables, if containing sensitive secrets running in development environments, can give attackers credentials that allow unauthorized data access, information leakage, and privilege escalation into production. There is a good place for environment variables to store configuration elements. They should just never be used for sensitive secrets.

This example application uses the Dotenv rails gem to load environment variables from .env This example app uses .env.local to load all of the populated environment variables contained in the file into the ENV constant that is dumped by Rack-mini-profiler. Take a look at the configuration that can also be seen in the Github repo for Hammer:

Beyond the risk of exposing sensitive environment variables through Middleware, there are a few other solid reasons why a developer should be aware of the risks inherent in this practice. This list below summarizes some of these risks from Diogo Monica :

- The risk of copying unencrypted environment variables files such as

.env.localinto central Git repositories by not properly using the .gitignore file. The risk of tribal knowledge, when new developers who didn’t set up the system don’t take the proper care in safeguarding these files containing environmental variables. Secrets are copied to a different system and exposed. - An application can grab the whole environment and print it out for debugging or error-reporting. Secrets can get leaked if they are not properly sanitized before leaving your environment.

- Environment variables are passed to child processes, which can lead to unintended access (i.e., a 3rd-party tool has access to your environment).

- When applications crash, it is common to store the environment variables in log files for debugging. This increases the risk of plain text secrets on disk.

Experimenting with ENV and Bash Environment

Before we jump into playing with some examples of ENV and environment variables, let’s review some laws of Ruby Environment variables. Honeybadger.io gives a fantastic tutorial on this and I’ll summarize:

- Every process has its own set of environment variables.

- Environment variables die with their process.

- A process inherits its environment variables from its parent.

- Changes to the environment don’t synch between processes.

- Your shell is just a UI for the environment variable system.

This example walks through the Hammer environment, inside the home directory of the Rails application.

Change into the working home directory of the Rails Hammer application:

$ cd /home/<username>/hammer

Grep for SECRET in the .env.local to see some of the environment variables we want to play with.

$ grep SECRET .env.local

You’ll see several of the crown jewel API keys. Now print your Bash shell environment variables with env. You’ll see all of the standard environment variables such as $HOME and $PATH. Verify with env | grep SECRET that those sensitive variables are not currently loaded in your Bash environment.

Run the Interactive Ruby Tool (irb) and we’ll see what happens. By default, irb will not see any of the sensitive environment variables exposed by ENV. This is because we need to use the Rails ‘dotenv’ gem to load the variables from an .env file. This shows that by default a Rails application inherits the environment variables of its parent process (the Bash shell) into ENV constant when a Ruby application is instantiated. But we need to specifically load extra environment variables into ENV hash constant in a special way, as those variables are not available by default. You’ll be able to see $PATH and $HOME but not any of the others.

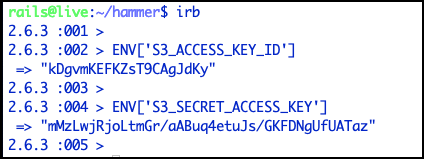

$ irb

> ENV

> ENV['PATH']

> ENV['S3_SECRET_ACCESS_KEY']

Instruct irb to use the dotenv gem to load the environment variables from the .env.local file. This command will load the environment variables into ENV, making them available to our irb ruby environment.

> require 'dotenv';Dotenv.load('.env.local')

Notice that all of the beautiful things are now available, the sensitive crown jewel API keys!

Verify that you have access to a couple of these beautiful, sensitive ENV things in your irb terminal!

> ENV['S3_ACCESS_KEY_ID']

> ENV['S3_SECRET_ACCESS_KEY']

Next, open up a new shell. Launch irb and try to list the sensitive environment variables stored in ENV.

Note that in the second shell’s irb session, no sensitive environment variables are listed. This is because of the way environment variables work. Every process has its own set of environment variables that are not automatically synced between processes.

Now to experiment with exporting these variables. If you put export in front of the syntax of the variables named in .env.local, and source the file, magic happens. This converts the local shell variables into environment variables available to ENV. Which is then available to any child Rails process instantiated from that bash shell. The hammer app includes a sample exported variable file for the purpose of playing with sensitive variables in a safe way – .env.local.exported . Let’s give this a try.

In the second shell, exit the irb session and type the source command. Then run env to list the environment variables in the bash shell:

$ source .env.local.exported

$ env | grep SECRET

Now in the second shell, re-launch irb and fetch the sensitive ENV variables.

$ irb

> ENV['S3_ACCESS_KEY_ID']

> ENV['S3_SECRET_ACCESS_KEY']

Amazing! You didn’t have to call Dotenv gem to automatically load into ENV. This shows you what Dotenv gem is doing — essentially sourcing the variables from the .env file when the environment is bootstrapped and loading them into ENV. ENV is then dumped via the Rack-mini-profiler Pretty Printer (pp) ruby class.

In this example, we ended up sourcing the exported variables to our bash shell. Once we exit the shell, the environment variables are not available to the next launched bash shell. If a developer were to add the commands to a shell init script such as .bashrc, this would persist these secrets to all users of the system in cleartext. This is another reason why this practice should be avoided.

Summary of Methods to Store Secrets

- Storing Secrets in Plaintext: Use Rails gem methods such as Dotenv or Figaro to store secrets in the environment, and access them through loading ENV. Other methods include rbenv-vars plugin and direnv. These are popular methods but developers should consider better security.

- SaaS Secrets Management Service: Use a service such as Vault, AWS Secrets Manager, and many others to synchronize and manage secrets within your app. This is a better approach than storing the secrets in plaintext, but keep in mind that you have to protect a super-secret SaaS API key that guards all of your secrets.

- Rails Encrypted Secrets: Starting with Rails 5.1, you can use encrypted secrets to provide better protection to your app credentials. They can be accessed with a special variable other than ENV key/value hash. Here is a good overview, and starting with Rails 6, you can do multi-environment credentials management. This is a more secure way than the first method and similar to the second one. This should keep the master encryption key on your Rails system instead of synchronizing it with a cloud SaaS.

Recommendations

Here are some recommendations for risk mitigation. These are meant to provide ideas and should be aligned with your DevOps processes.

- Remove the rack-mini-profiler gem on all systems connected to the public Internet.

- On systems requiring Rack-mini-profiler with public Internet access: Implement strong access control by whitelisting/firewalling IP addresses to only allow developer workstations to access the web application.

- Use the RackMiniProfiler access control to authorize and whitelist requests. RackMiniProfiler has an authorization_mode to whitelist in production. Reference the Access control in non-development environments section of the Readme.

- Use Encrypted Secrets and avoid using the environment variables with ENV to store sensitive credentials. The best method to perform this locally is Rails Encrypted Secrets. This will avoid loading sensitive variables into ENV where the risk increases that they can be inadvertently exposed.

Conclusion

Middleware such as Rack-mini-profiler provides excellent features to developers for improving the speed of Rails applications; however, security controls must be applied to ensure that secrets are properly protected in your application and not leaked to adversaries.

A wise Cyber Security professional made this simple yet powerful statement:

We all need to work together. Any weakness is a weakness that needs to be fixed, let’s work together to fix things.

References

https://github.com/MiniProfiler/rack-mini-profiler

https://www.speedshop.co/2015/08/05/rack-mini-profiler-the-secret-weapon.html

https://www.honeybadger.io/blog/securing-environment-variables/

https://www.honeybadger.io/blog/securing-environment-variables/

https://diogomonica.com/2017/03/27/why-you-shouldnt-use-env-variables-for-secret-data/

https://stackoverflow.com/questions/61821207/rails-environment-variables-with-rack-mini-profiler

https://medium.com/craft-academy/encrypted-credentials-in-ruby-on-rails-9db1f36d8570